Collaborations Between Two National Laboratories and the OSG Consortium Propel Nuclear and High-Energy Physics Forward

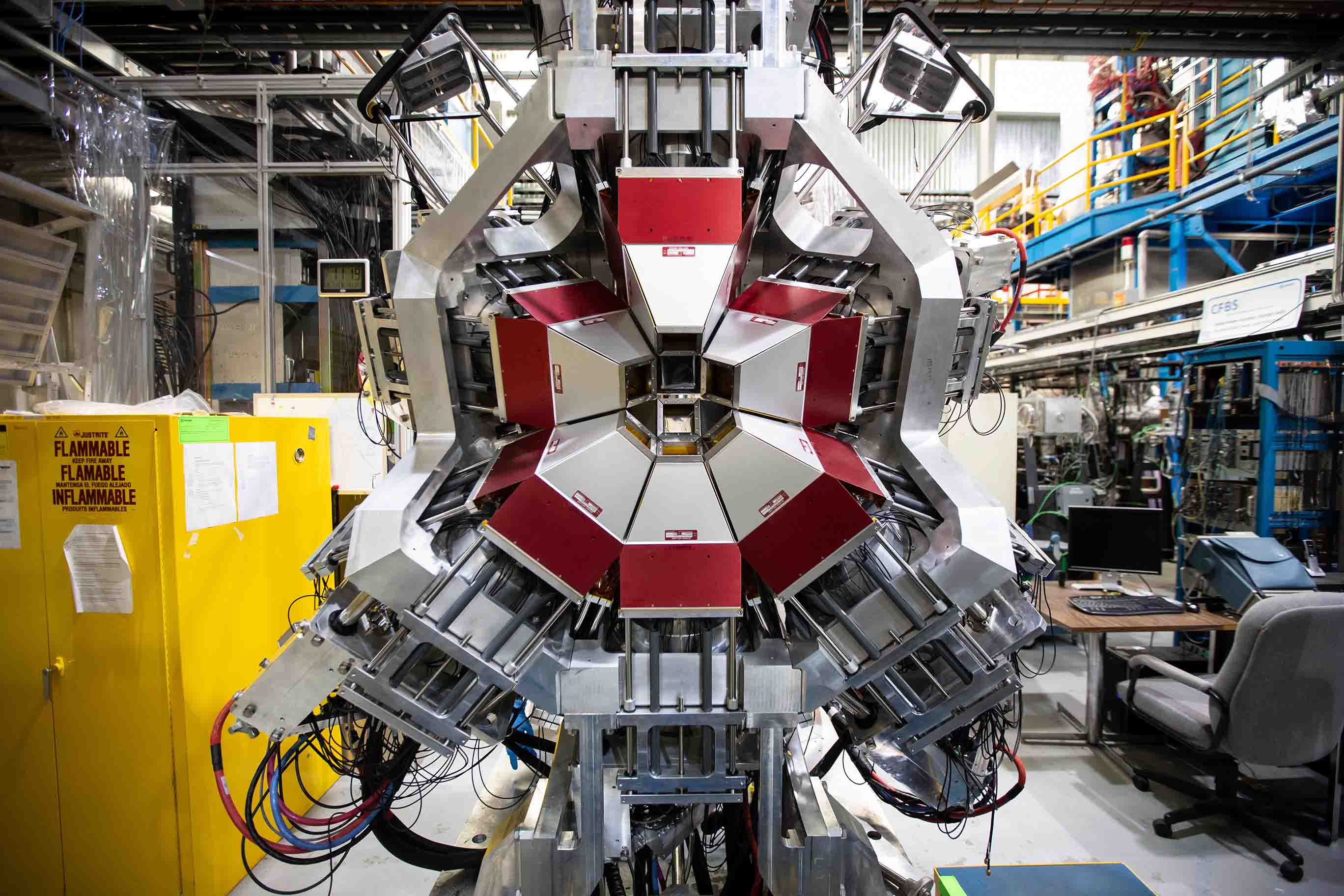

Seeking to unlock the secrets of the “glue” binding visible matter in the universe, the ePIC Collaboration stands at the forefront of innovation. Led by a collective of hundreds of scientists and engineers, the Electron-Proton/Ion Collider (ePIC) Collaboration was formed to design, build, and operate the first experiment at the Electron-Ion Collider (EIC). This experiment aims to construct the world’s most advanced particle detector, capable of analyzing collisions between electrons and protons or other atomic nuclei.

“They are building a detector that can slide seamlessly into EIC’s infrastructure. When these collisions occur, they will capture a wealth of physics data that advances our understanding of high-energy nuclear interactions. The outcomes of these collisions allow us to explore new frontiers in physics” reports Pascal Paschos, the OSG Consortium Facilitator who supports the work of ePIC. Paschos oversees the collaborations’ access to computational capacity necessary to conduct these experiments.

The EIC, developed by the collaboration between Brookhaven National Lab (BNL) and Jefferson Lab (JLab), will be the world’s first electron-nucleus collider of its kind. It features two intersecting accelerators—one generating a powerful polarized electron beam and the other a high-energy beam of polarized protons or heavier atomic nuclei. However, ePIC faces the challenge of validating the detector design for integration with the EIC. Paschos explains, “To validate the detector design, throughput capacity is required to model and experimentally simulate the detector. The goal is to evaluate how the detector would respond to signals generated from theoretical collisions included in their parameter files.”

“This project isn’t new,” adds Dr. Wouter Deconinck, associate professor at the University of Manitoba and Deputy Software and Computing Coordinator (SCC) for Operations at ePIC. “Concepts for an electron-ion collider have been in development for 20 or 30 years, aiming to include a polarized ion beam.” Drawing on his experience at the HERA electron-proton collider and post-graduate work in electron polarimetry, Deconinck, alongside BNL postdoctoral fellow Sakib Rahman, explains, “Since 2008, we’ve been evaluating the computing and software stacks needed for an electron-ion collider. Planning for operation into the 2030s necessitates future-proof and modular development to incorporate emerging technologies.”

Achieving a unified system is one important goal for the project. ePIC requires an infrastructure capable of simulating and gathering essential data for their design. One option was the OSPool, a shared computing capacity available to researchers affiliated with US academic institutions. Deconinck and Rahman considered other computing infrastructures for these simulation jobs. Deconinck notes, “We evaluated the OSPool and compared it with the EIC pool of resources available at JLab, BNL and the Digital Research Alliance of Canada (the Alliance.) Both pools were capable of handling about 2000 jobs at a time.” Ultimately selecting the OSPool, Deconinck notes,“We saw it as a way to convince JLab to allocate jobs to the OSPool indirectly, transferring jobs to the Alliance, and continuing to submit to the OSPool. The primary advantage was achieving a unified interface across all these sites.”

Rahman also emphasizes OSPool’s role in the integrated system, stating, “Previously, someone had to create accounts on every site to submit jobs. Now, running production campaigns, others need an account on one PATh operated Access Point, with their work credited to ePIC. This detachment from individual operators and alignment with the project as a whole significantly reduces onboarding time.”

Scalability is also an essential requirement of the project. “Typically, we consider the time to simulate one event, estimated at 10-15 seconds per event using standard computing software,” Deconinck explains. “Based on this and statistical projections for the number of events to analyze, we calculate our total computing needs. For each reaction channel, we typically examine 5 to 10-20 million events to determine if a detector configuration yields desired results.”

Deconinck also reports that “One aspect I found immensely valuable was the initial interaction with the OSPool. Upon setting up an account, I received personalized attention from the OSG Research Computing Facilitation team, with someone guiding me through the process and inquiring about my approach. What truly made a significant impact were the office hours provided. There were weeks where I attended these sessions twice, and without fail, there was always someone available to offer assistance and feedback. This support was instrumental in getting us started.”

The OSPool enables Deconinck, Rahman, and teams to collaborate seamlessly worldwide in partnership with 173 institutions. “The engagement of ePIC with the OSG fabric of services brings two major laboratories into the fold, helping coordinate between them for the delivery of science,” adds Paschos. “The collaboration itself extends beyond individual PIs aiming to advance scientific outcomes; it encompasses engagement at all levels, from technical teams to geographically diverse points of interest.”

Collaboration is the cornerstone of success in multi-institutional projects like these. The synergy between the OSPool, two major national laboratories, and international teams exemplifies the power of collective effort in propelling physics science forward. Overcoming challenges and achieving groundbreaking discoveries requires a village of dedicated scientists, engineers, and collaborators from diverse backgrounds. Much like the “glue” binding visible matter, teamwork unites the ePIC Collaboration, magnifying their impact beyond the lab. Their journey powered by the OSPool capacity underscores the transformative power of cooperation and sharing in unraveling the mysteries of our universe.