“Becoming part of something bigger” motivates campus contributions to the OSPool

A spotlight on two newer contributors to the OSPool and the onboarding process.

A campus’ motivation to contribute computing capacity to the Open Science Pool (OSPool), an internationally recognized resource supporting scientific research, can be distilled down to the desire to “become part of something bigger,” says OSG Campus Coordinator Tim Cartwright. The “something bigger” refers to national cyberinfrastructure. By sharing idle, unused capacity with institutions nationwide, contributors enhance the OSPool and contribute to the science executed by researchers utilizing this pool.

Approximately 80% of OSPool member schools donate capacity to the OSPool after receiving a Campus Cyberinfrastructure (CC*) grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF), which requires dedicating 20% of computing capacity to a larger entity like the OSPool. Campuses choose the OSPool to provide this capacity, in part, because it is a readily implemented approach to meet this requirement without impeding research happening on-campus. Leading the onboarding efforts, Cartwright and OSG staff have developed a straightforward, fairly easy-to-implement approach for campuses who wish to contribute capacity. Cartwright describes the growth of the OSPool as “an incredible boom” since 2020. In the past year, about 70 institutions have contributed to the OSPool.

A closer look at the journey of two new OSPool members, Montana State University and The University of Michigan-Ann Arbor illustrates the motivations and experiences of campuses when integrating some of their capacity into the OSPool.

Montana State University

Coltran Hophan-Nichols, Director of Systems and Research Computing at Montana State, approached the OSG Consortium before applying for a Campus Cyberinfrastructure (CC*) grant. Familiar with the OSPool, he knew it would be a logical choice to fulfill the 20% requirement.

Along with growing student interest in HPC and HTC, Montana State needed to provide new computational resources for fields such as quantum science, artificial intelligence and precision agriculture that were expanding rapidly. Hophan-Nichols knew that the OSPool could augment these much-needed resources for researchers while allowing Montana State to give back capacity that would otherwise sit idle. “We pursued the OSPool because it provides national-level access while being flexible [with allocations],” Hophan-Nichols said. “We’re able to contribute significant capacity without impacting what researchers here can do.”

“The integration itself is a relatively simple process,” Cartwright said, consisting of two meetings with the campus staff and Cartwright, plus OSG Operations team members. The first meeting is a “kickoff,” where Cartwright and the campus staff talk through the technical aspects of integration. Much of the work occurs between the two meetings, with campus staff setting up access to their cluster and OSG staff preparing connection and service configuration. The second meeting is the actual integration to the OSPool, which involves setting up new OSG services to connect the site and manually verifying correct operations.

During the integration meeting, the OSG team verifies that access to the site works as expected, that manual tests succeed and that the end-to-end automated processes function. To alleviate safety concerns, Cartwright explains that connections into the campus system are limited to one common service (SSH) and even then, only to one computer within the campus. All other networks are established from within the campus to external systems. “We have tried to make it as minimally intrusive as we possibly can to work with individual campuses and what their security teams are comfortable with,” he said.

Regardless of how much is done to prepare, some hiccups occur. Montana State “had to make minor tweaks to configuration changes, which ultimately sped up transfer for OSPool and local transfers,” Hophan-Nichols said. The OSG Operations team and Cartwright also try to identify common issues and troubleshoot them before the integration.

After making sure that connections were working and jobs were starting to run, Montana State kept its contributed capacity small to ensure everything was working properly. Since then, Hophan-Nichols has worked with Cartwright to scale up availability. When they first joined, they were contributing fewer than 1,000 jobs per day. Now, they are contributing up to 181,000 jobs per day and over 2.53 million jobs in total from January through March.

“It’s been mutually beneficial,” Hophan-Nichols said. “There is next to no impact on the availability of capacity for local researchers and we still have a significant chunk of resources we’re able to contribute to the OSPool.”

The Michigan HORUS Project

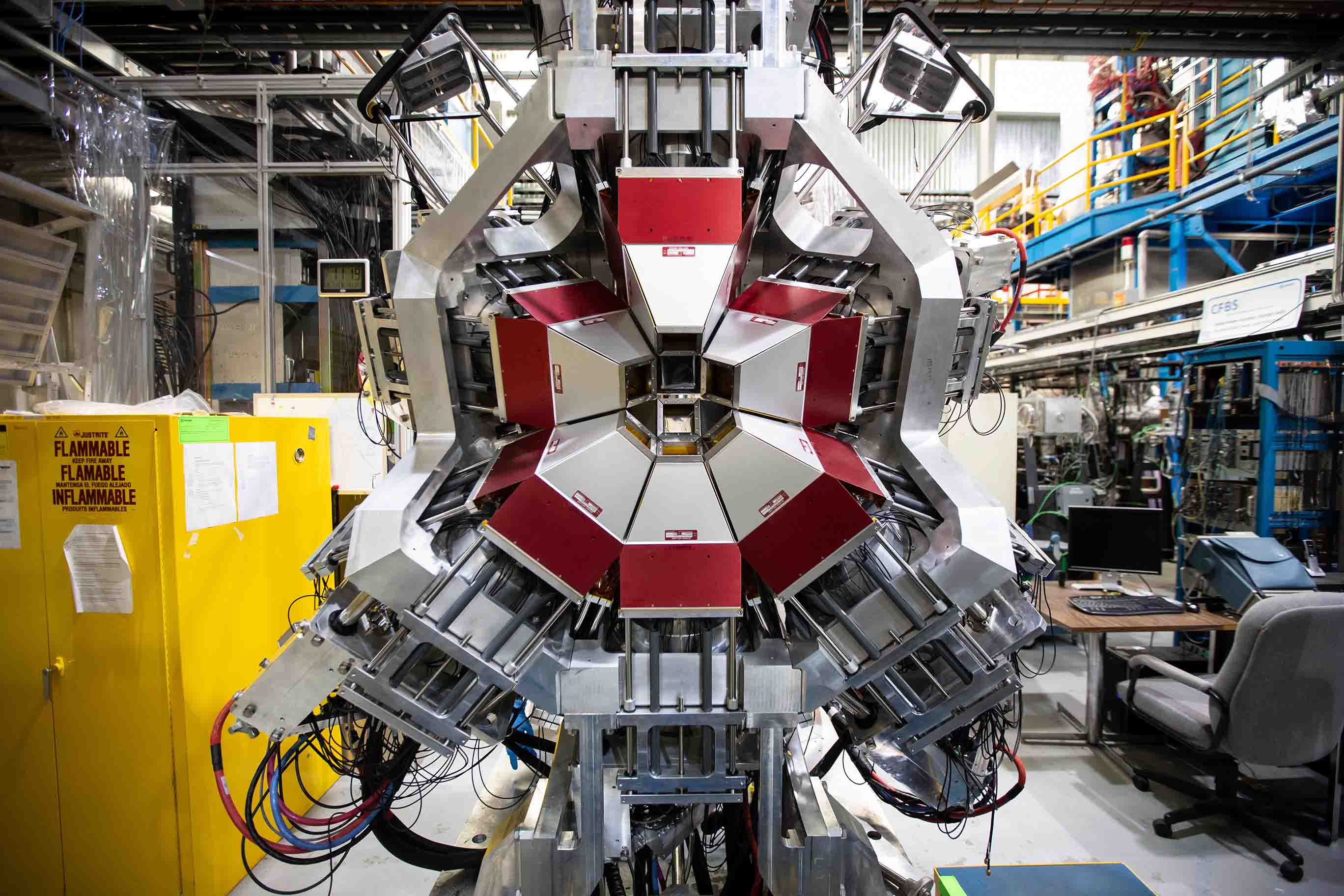

The HORUS Project, a joint effort among the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor (U-M), Merit Networks, Michigan State University and Wayne State University (WSU), integrated some of their computing capacity into the OSPool in January 2024. The HORUS regional compute project, building upon the previous OSiRIS project, exists to grow statewide computing and storage capacity, as well as contribute to open capacity. Shawn McKee, a Research Scientist at U-M, and his colleagues at Merit and WSU secured a CC* grant to create HORUS and begin contributing capacity to the OSPool. “We had been planning to join for a while, but we managed to get everything operational earlier this year,” he said.

HORUS project team members faced unique technical challenges trying to combine their existing statewide system with the broader OSPool. Between the initial meeting and the onboarding, McKee and his colleagues established a secure transfer node for the OSG Consortium to use. Similar to Montana State, the HORUS project engineers have a strong background in research computing which made the integration straightforward. In the end, connecting via SSH jump hosts and routing jobs to all three campuses only took 40 minutes. “Pretty quickly, ‘Hello World!’ worked right away and users could start using it,” McKee recalled.

McKee also values the OSPool for its ability to smoothly fulfill the 20% requirement for their CC* grant. Beyond this, the OSPool offers more capacity to researchers and accesses capacity from the HORUS project that would otherwise sit idle. “It was great to have the OSG Consortium come in and start utilizing large memory and compute nodes that were only lightly loaded,” McKee said. “There was significant idle time that now the OSPool can use.”

Across the HORUS project, McKee identified at least four researchers interested in using idle resources in the OSPool and is excited to keep growing campus involvement. At U-M, PI Keith Riles uses the OSPool for work in gravitational physics. Through the OSPool, Riles has run over 200,000 jobs across 52 facilities. At WSU, PI Chun Shen uses the OSPool for work in nuclear physics, utilizing its capacity to run over 13 million jobs across 41 facilities.

Once campuses are onboarded, OSG staff continue to collaborate with campus personnel. Beginning in February, they introduced OSG Campus Meet-Ups, a weekly campus-focused video conference where campus staff can talk and learn from each other or OSG staff. Throughput Computing and OSG School, two events in the summer, also offer in-person opportunities for campus staff to visit OSG staff and other campuses on the University of Wisconsin–Madison campus.

Prospective Campuses

The NSF CC* program provides unique access to resources and funding to improve campus research. CC* applicants can receive a letter of collaboration from one of the PATh PIs for submission. For more information, visit the PATh website instructions.