Expanding, uniting, and enhancing CLAS12 computing with OSG’s fabric of services

A mutually beneficial partnership between Jefferson Lab and the OSG Consortium at both the organizational and individual levels has delivered a prolific impact for the CLAS12 Experiment.

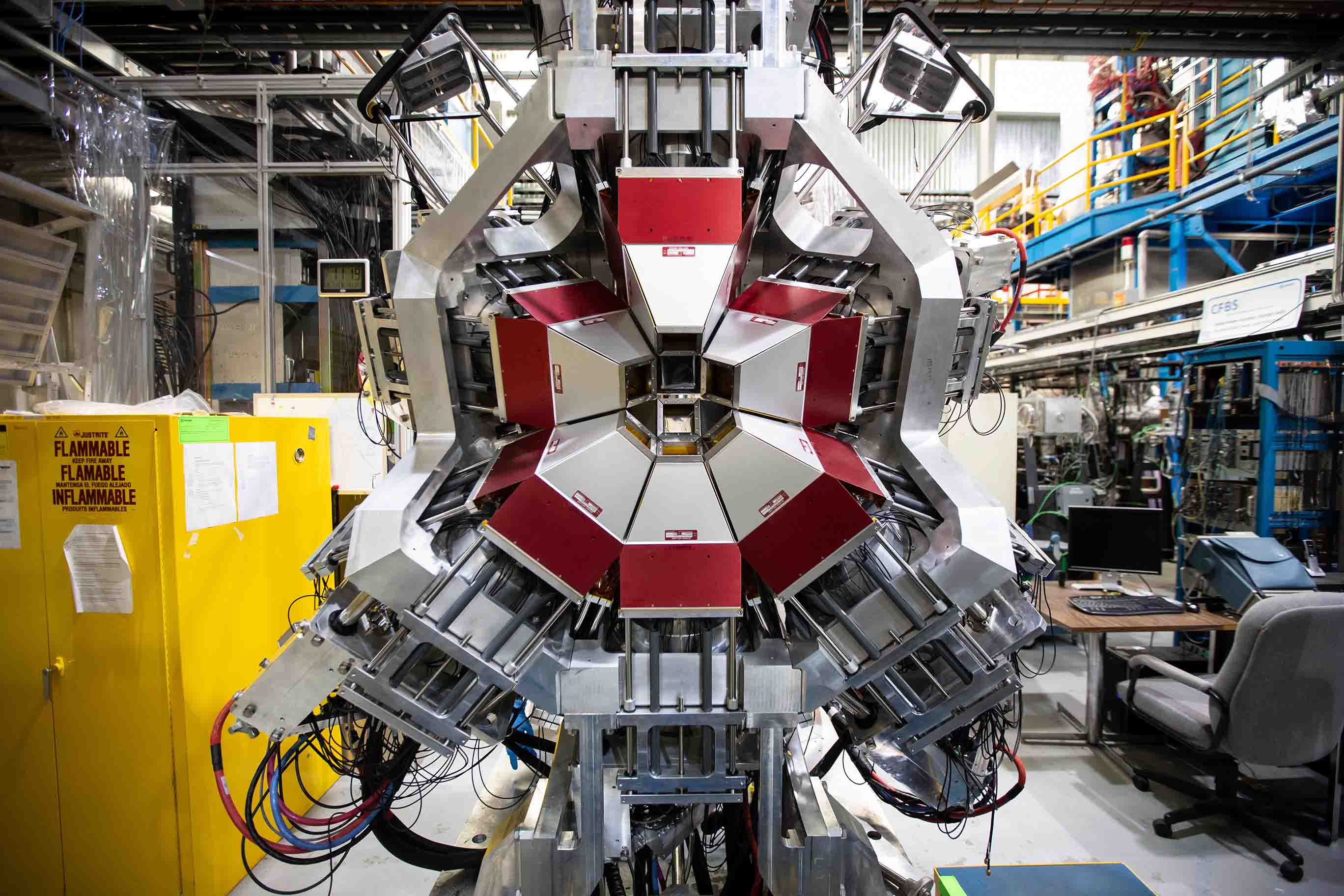

Twenty-five feet underground within the U.S. Department of Energy’s Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility in Newport News, Virginia, electrons circulating at nearly the speed of light form a beam that’s as narrow as a single strand of human hair. Traveling around a racetrack-shaped accelerator five times in about 22 millionths of a second, electrons in this beam are directed into a target material, where they collide with protons and neutrons that reside inside the nuclei of the target atoms. These collisions produce an array of new particles, which ricochet out of the target material and into a unique detector that measures the particle’s momentum and speed to determine its mass and identity.

At first, these quantum interactions may seem incomprehensible in human dimensions, but these marvels of physics –– and the computational approaches required to study them –– have brought together people, groups, and institutions across nations and scientific disciplines. The racetrack-shaped accelerator at Jefferson Lab, officially known as the Continuous Electron Beam Accelerator Facility (CEBAF), attracts approximately 1,500 scientists from around the world, all visiting Jefferson Lab to conduct experiments. The one-of-a-kind detector known as the CEBAF Large Acceptance Spectrometer, or the CLAS detector, is the namesake of the CLAS Collaboration, a group of over 200 collaborators from more than 40 institutions that span a total of 8 countries. To manage their ever-growing amounts of data, geographically-distributed collaboration, and complex workflows, the CLAS Collaboration partners with the OSG Consortium in expanding, uniting, and enhancing their experiment.

Researchers within this collaboration all strive to understand atomic structure, yet their individual topics of study are diverse, ranging from the multi-dimensional distribution of quarks and gluons inside a proton, to the binding interactions within a complex nuclei. In pursuit of this research, scientists in the Collaboration have used 42 million core hours through OSG services in the past year. This number is impressive in itself, yet the amount of communication and coordination required to achieve this level of computational throughput is far more extraordinary. These collaborative endeavors have a long history, dating all the way back to the inception of the OSG Consortium.

The foundations of a partnership

After ten years of construction, Jefferson Lab began operations in 1997. This marked the beginnings not only of the CLAS experiment, but also the collection of other physics experiments that call Jefferson Lab home. Soon after their launch, Jefferson Lab contributed as a founding institution for the OSG Consortium. They participated in the formation of OSG’s bylaws but didn’t leverage OSG’s services because it wasn’t an appropriate fit for their experiments at the time. In April of 2018, however, Jefferson Lab rejoined the OSG Consortium in full force to pursue opportunities for the GlueX experiment, and eventually also for the CLAS Collaboration’s new and upgraded experiment called CLAS12.

This resurgence on the organizational level all stems from the actions of individual people. Before Jefferson Lab rejoined the OSG Consortium, Richard Jones, a principal investigator (PI) at the University of Connecticut who is involved in the GlueX experiment, began exploring OSG’s services. Jones not only introduced the benefits of OSG to GlueX, but also to Jefferson Lab more broadly. After OSG’s workflow and infrastructure proved to be scalable for GlueX, members of the CLAS Collaboration became interested in OSG’s fabric of services too. Frank Würthwein, OSG Executive Director, interprets this process as a “flow of engagement that followed the social structures that the relevant parties were embedded in. Basically, it’s a campus word-of-mouth.”

Frank Würthwein, OSG Executive Director. (Photo by Owen Stanley).

This partnership was cemented when Würthwein visited Jefferson Lab to discuss opportunities for both the GlueX and CLAS12 experiments. The resulting partnership that exists today has proven to be notably symbiotic. In fact, Würthwein professes that the partnership with Jefferson Lab has been absolutely central to OSG’s mission: “Jefferson Lab and the CLAS Collaboration have helped us multiply our message, improve our tools, and ultimately advance open science itself. They have played an important role in making us a better organization.” Likewise, the CLAS Collaboration has been able to expand their computing capacity, unite their computing resources, and enhance their science as a result of working with OSG.

Expanding computing resources

On a fundamental level, OSG’s fabric of services provides the CLAS Collaboration with additional computing power through the Open Science Pool (OSPool) –– an asset that was vital after transitioning to a new, upgraded version of the experiment in 2018. Compared to the original experiment, the electrons blasting into the target material in the new experiment carry twice the energy –– 12 billion electron volts to be exact. This new experiment, coined ‘CLAS12’ to signify this energy increase, also engendered a tenfold increase in computing demand. While Jefferson Lab’s in-house computing resources are extensive, the sheer amount of data produced in the CLAS12 experiment is substantial. Today, the experiment generates about 1 petabyte of data each year.

To put this number into perspective, 1 petabyte is equivalent to twenty million four-drawer filing cabinets completely filled with text, or 13.3 years of HD-TV video. That’s a lot of data to manage.

Nathan Baltzell, Jefferson Lab Staff Scientist.

Nathan Baltzell, a Jefferson Lab Staff Scientist who organizes software efforts for CLAS12, describes how staff at Jefferson Lab responded to this data dilemma: “When this newer era of experiments started four years ago, projections were that we would absorb all our local computing resources crunching the real, experimental data. It was critical to be able to run simulations somewhere else.”

That somewhere else became the capacity offered by the OSG. Each job submitted by CLAS12 researchers contains about 10,000 different monte-carlo simulations and runs for roughly 4-6 hours on a single core. Once submitted to an OSG Access Point, CLAS12 jobs either run on opportunistic or dedicated resources. Opportunistic resources, or resources contributed to the common good of all open science via the OSPool, have provided the CLAS12 experiment with roughly 33 million core hours in the past year. On the other hand, dedicated resources –– those exclusively reserved for the CLAS12 experiment –– supply the Collaboration with about 9 million core hours annually. These dedicated resources have undoubtedly played a role in expanding computing capacity, but they also have proven instrumental in uniting computing resources of the CLAS Collaboration.

Uniting geographically-distributed computing resources

Beyond expanding the computing resources available to the CLAS12 experiment, OSG services have also played a role in uniting the CLAS Collaboration’s existing computing resources scattered around the globe. Hundreds of collaborators belonging to many different institutions in a collection of countries translates to more total computing resources at the Collaboration’s disposal. However, accessing this swath of distributed resources, installing the necessary software, and ensuring everything runs smoothly proved to be a logistical headache that worsened as the CLAS Collaboration’s software evolved and became more sophisticated.

Raffaella De Vita, INFN Staff Scientist and Software Coordinator of the CLAS Collaboration.

Thankfully, OSG’s services could serve as a unified pool that would unite the CLAS Collaboration’s computing resources and bypass the logistical bottlenecks. Raffaella De Vita, Software Coordinator and former Chair of the CLAS Collaboration, comments on the value of this approach: “The idea of using OSG services to basically collect resources that our institutions could provide and make them in a unified pool that could be used more efficiently, became very appealing to us.”

Today, 6 CLAS Collaborators with their own computing centers have joined the OSPool to provide dedicated resources to the experiment in a more efficient manner. These institutions include Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Glasgow University, Grille au service de la Recherche en Ile de France (GRIF), Lamar University, Compute Canada, and Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare (INFN). De Vita, a Staff Scientist at INFN, was personally involved in coordinating the addition of INFN’s computing resources to the OSPool. She considers the process to be quite successful from her perspective: “People at OSG took care of creating the connection and working with our computing center staff, and I basically just had to send some emails.” Zooming out on impacts to the CLAS Collaboration more broadly, De Vita adds, “it’s been an excellent way to get members of the collaboration to contribute not only with manpower, but also with computing resources.”

Enhancing science and improving workflows

Finally, collaboration among OSG and Jefferson Lab staff has resulted in improved workflows, streamlined submissions, and enhanced science. The HTCondor Software Suite (HTCSS), which was developed at UW-Madison and is used to automate and manage workloads, coordinates the submission of CLAS12 jobs. Containers, which function naturally on the OSPool, are used to create custom software environments for CLAS12 jobs.

Maurizio Ungaro, Jefferson Lab Staff Scientist.

When asked about workflows and job submissions, Maurizio Ungaro, a Jefferson Lab Staff Scientist who helps coordinate CLAS12’s monte-carlo simulations, expresses: “This is actually where OSG services are really useful. Containers allow us to encapsulate the software that we run, and HTCondor coordinates the submission of our jobs. Because of this, we’re able to solve two problems: one being CPU usage, and the other being simulation organization.”

Before they began using OSG Access Points, CLAS Collaborators used to write their own submission scripts, a challenging task that involved many moving parts and was prone to errors. Now, through coordination with OSG staff, Ungaro and his team have been able to package the array of tools in a user-friendly web portal. Describing the impacts of this new interface, Ungaro explains: “Now, collaborators are able to submit jobs using the web portal, even from their phone! They can choose from several experiment configuration options, click the submit button, and within a few hours the results will be here at Jefferson Lab on their user disk space.” In essence, this web portal streamlines the process of job submission, all so that CLAS Collaborators can grow and improve their physics.

A legacy of multi-scale collaboration

The partnership between Jefferson Lab and the OSG Consortium is a story of many dimensions. Projects of this scale are rarely a seamless production system in which all components are automated. They require hard work and close coordination, at both the organizational and individual levels.

On the individual scale, consistent, day-to-day interactions accumulate to instill a lasting impact. OSG staff participate in Jefferson Lab’s weekly meetings, engage in one-on-one calls, and organize meetings to resolve issues and support the CLAS12 experiment. Reflecting on the culmination of these interactions, Ungaro would characterize his experience as “nothing short of incredible.” He adds: “I can see not just their technical expertise, but also how they’re really willing to help, happy to contribute, and grateful to help our science.”

Pascal Paschos, OSG Collaborations Facilitator.

Pascal Paschos, the OSG Area Coordinator for Collaboration support who works closely with the CLAS12 Collaboration, sees the experience as an opportunity for growth: “OSG doesn’t merely provide a service to these individual labs; it’s also an opportunity for us to grow as an organization by identifying what we have done well in our partnership with Jefferson Lab to enable such a prolific production from one of their experiments.”

Ultimately, the CLAS experiment as it exists today is a product of cross-coordination between Collaboration members, executive teams, and technical staff on both sides of the partnership, all working together to make something happen. As Paschos phrases it: “At the end of the day, you’re looking at partnerships –– not between institutional entities –– but between people.”

…

Learn more about Jefferson Lab and the OSG Consortium, and browse all publications from the CLAS Collaboration.